More Learning Is Not Making Us Wiser

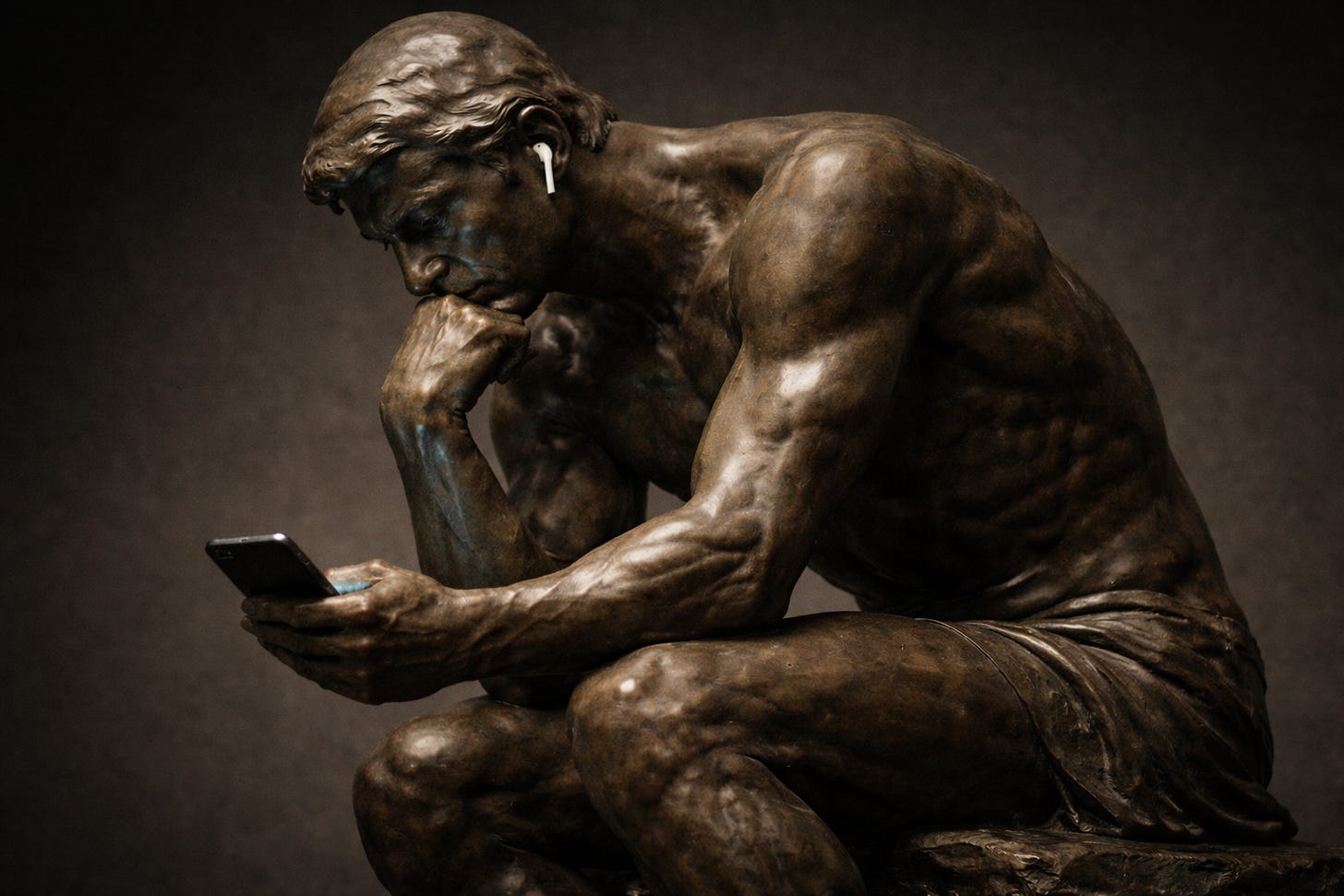

Our addiction to information and the cost of endless inquiry

I can’t keep up with all the content that is suggested to me these days. I don’t want to learn new things all the times. As out of character as this sounds, I have come to terms that I am just not in a season of constant learning currently; which has given me some helpful perspective.

We live in a moment where an infinite catalog of information sits at our fingertips. Knowledge no longer asks for a set time or a chosen place. It travels with us. We listen while we drive, absorb while we exercise, and process information in the spaces that once belonged to silence. There is always something else to understand, another voice explaining what we have not yet considered, another layer inviting us to keep clicking, keep learning.

In the Exodus story, Israel is guided by a cloud by day and a fire by night. When the cloud moves, the people move. When it settles, they stop. They pitch their tents. They stay. Faithfulness is not measured by constant motion, but by attentiveness. Knowing when to wander matters. Knowing when to settle matters just as much (Exodus 13:21–22; Numbers 9:17–23).

I have been thinking about that distinction a lot lately. Not because I have lost my appetite for truth, but because I am increasingly aware of how restless we have become in our pursuit of it. We live in a moment where an infinite catalog of information sits at our fingertips. Knowledge no longer asks for a set time or a chosen place. It travels with us. We listen while we drive, absorb while we exercise, and process information in the spaces that once belonged to silence. There is always something else to understand, another voice explaining what we have not yet considered, another layer inviting us to keep clicking, keep learning. The dissemination of information has become ambient, almost compulsory, and we rarely stop long enough to ask what this constant exposure is actually doing to our souls.

Part of what makes this moment difficult to name is that we inherited a way of thinking about knowledge long before we ever chose it. The Enlightenment trained us to trust information as a moral good, to believe that more knowledge naturally produces better people, healthier societies, and wiser faith. Learning came to be seen as neutral at worst and virtuous at best. Questions became signs of humility. Certainty became suspect. Over time, even faith was quietly reshaped around this assumption. Jesus’ command to love God with heart, soul, and mind was rightly reclaimed by intellectuals emphasizing worship via mental ascent as a corrective to forms of faith that had drifted toward feeling alone (Matthew 22:37). But what began as balance slowly became an overcorrection. The mind was elevated, and the heart and soul were diminished. Biblical faith never made that separation. When faith is reorganized primarily around cognition, we lose contact with the mystical heart where trust, intuition, and discernment are formed.

These are not anti-intellectual claims. They are sober assessments of excess. They name what happens when the pursuit of knowledge loses contact with the limits of the human soul.

Biblical wisdom tells a different story. In Proverbs, wisdom is not treated as raw information to be accumulated, but as something that calls out, dwells with the faithful, and must be received inwardly (Proverbs 1:20–23; Proverbs 2:1–5). The invitation is not simply to understand, but to trust. “Trust in the Lord with all your heart,” we are told, rather than leaning solely on accumulated understanding (Proverbs 3:5). The Psalms repeatedly link wisdom to waiting, silence, and patient attentiveness to God’s presence, suggesting that knowing often emerges from stillness rather than activity (Psalm 37:7; Psalm 46:10).

Ecclesiastes presses the question even further. It does not dismiss learning outright, but it does refuse to romanticize it. The Teacher observes that “in much wisdom is much grief,” and that increasing knowledge often increases sorrow rather than peace (Ecclesiastes 1:18). Near the end of the book, we are warned that “of making many books there is no end, and much study is a weariness of the flesh” (Ecclesiastes 12:12).

These are not anti-intellectual claims. They are sober assessments of excess. They name what happens when the pursuit of knowledge loses contact with the limits of the human soul. Even Job, who demands answers, is finally led not into explanation but into silence and trust before the presence of God (Job 38–42). Wisdom in Scripture is relational, intuitive, and formed over time. It is carried in the heart, shaped by obedience, prayer, and lived attentiveness. When life is reduced to learning alone, we lose contact with that mystical center where discernment, communion, and peace are actually formed.

There is something quietly countercultural about saying you are settled. In a world that prizes openness, revision, and perpetual learning, non-negotiability is often treated as moral failure.

What we are living inside now feels like the natural outcome of a long habit of mind that equates growth with knowledge. Learning has become synonymous with progress. Curiosity has become a moral posture. Technology has removed natural limits, and engagement no longer knows when to stop. Everything can remain open, provisional, and under review. For certain personalities, especially those who find safety in understanding, this environment feels endlessly compelling. It also exacts a quiet cost. The soul grows tired of permanent transit.

You cannot always stay on the go. You cannot keep roaming, wandering, and deconstructing without end. Eventually, the soul begins to desire something else. Not certainty, and not closure, but rest. A place to stop for a while. A place to settle, even briefly. An outpost rather than a destination. A waypoint that others might recognize and return to.

There is something quietly countercultural about saying you are settled. In a world that prizes openness, revision, and perpetual learning, non-negotiability is often treated as moral failure. To stop examining can sound like refusal. To hold fast can sound like fear. And yet every life, if it is going to be lived with integrity, eventually arranges itself around what will not be renegotiated.

If you find yourself tired in this moment, worn down by the constant flow of information, explanations, and invitations to reconsider everything, there is nothing wrong with you.

Non-negotiable beliefs, convictions, and values are not a sign that growth has ended. They are often the sign that formation has begun.

In practice, this kind of settling often shows up as a boundary. The decision not to engage every challenge. The freedom to say that something is not up for discussion. Not out of fear or fragility, but out of clarity. Boundaries like these are not a rejection of others, and they are not a refusal to learn. They are simply an acknowledgment that not every belief needs to remain publicly negotiable in order to remain alive.

If you find yourself tired in this moment, worn down by the constant flow of information, explanations, and invitations to reconsider everything, there is nothing wrong with you. You may not be closed. You may be full. Sometimes the exhaustion is not a signal that you need more input, but that you have already received enough. And sometimes wisdom looks like honoring that limit, staying where you are for a while, and letting what you already believe do its quiet work.

I am reminded of the verse that says "Be still and know that I am God." We can chase knowledge until the cows come home, but without wisdom to temper the knowledge, it is a dangerous thing. Yes, we can build a bomb big enough to destroy the whole earth. But should we?

In my Dungeons and Dragons days, I learned the difference between wisdom and intelligence. Intelligence tells you it's raining. Wisdom tells you to get out of the rain. Two entirely different things, but each relying on the other to produce meaningful results.