The Gospel for The Deconstructing

What Pastors and the Church Can Learn from Thomas’s Doubt

When I was in the throes of deconstruction, Skillet's John Cooper took the stage at a Christian concert and declared that it was time to go to war. Not against sin, or injustice, or despair—but against deconstruction. He framed it as a threat to the faith, something dangerous to be stamped out. And many in the crowd cheered. I remember watching it unfold, not with anger, but with sadness. Close friends of mine echoed his posture in quieter ways. Some grew uneasy when I brought up what I was wrestling with. Others recoiled altogether, as if the mere mention of the word was a spiritual contagion. It became clear to me that deconstruction wasn't just controversial—it was relationally risky.

This year's Lectionary reading for the Sunday after Easter was John 20. There are two resurrection stories in John's account. One happens in the garden, in the light of morning. The other unfolds that night, behind locked doors, under the weight of fear and uncertainty. Both are resurrection stories, but they don’t feel the same. One is full of recognition and rejoicing. The other is quiet, cautious, and unresolved.

Later on that day, the disciples had gathered together, but, fearful of the Jews, had locked all the doors in the house. Jesus entered, stood among them, and said, “Peace to you.” Then he showed them his hands and side. The disciples, seeing the Master with their own eyes, were awestruck. Jesus repeated his greeting: “Peace to you. Just as the Father sent me, I send you.” Then he took a deep breath and breathed into them. “Receive the Holy Spirit,” he said. “If you forgive someone’s sins, they’re gone for good. If you don’t forgive sins, what are you going to do with them?”

But Thomas, sometimes called the Twin, one of the Twelve, was not with them when Jesus came. The other disciples told him, “We saw the Master.” But he said, “Unless I see the nail holes in his hands, put my finger in the nail holes, and stick my hand in his side, I won’t believe it.”

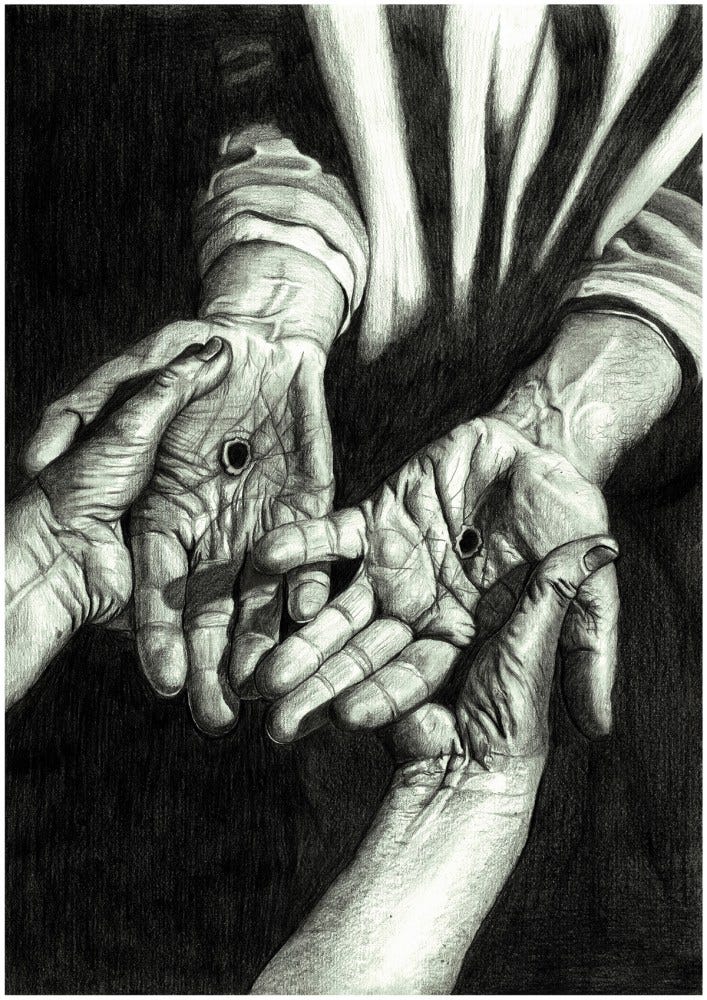

Eight days later, his disciples were again in the room. This time, Thomas was with them. Jesus came through the locked doors, stood among them, and said, “Peace to you.” Then he focused his attention on Thomas. “Take your finger and examine my hands. Take your hand and stick it in my side. Don’t be unbelieving. Believe.” Thomas said, “My Master! My God!” Jesus said, “So, you believe because you’ve seen with your own eyes. Even better blessings are in store for those who believe without seeing.”

John 20:19-39 MSG

The story of the locked room, the doubt, and the uncertainty feels painfully familiar to when I was deconstructing. Because while others seemed to live on with faith questions with ease, I remained behind closed doors, holding fragments of what used to be certain. And yet, deep down, I knew I was on the right path. Even if it disturbed my fellow Christians. Even if it disrupted the tidy categories that once held my confidence. The questions that rose in me weren’t rooted in rebellion. They came from grief, from honesty, from the painful realization that the framework I’d been handed could not carry the full weight of my experience. I wasn’t trying to destroy anything. I was trying to survive.

If the weight of that wasn’t hard enough, the feeling that I no longer had a place at the table that once nurtured my soul ensured that this crisis would inevitably be existential. It’s one thing to doubt a doctrine. It’s another to doubt your own belonging. That’s where the shame creeps in. That’s where silence takes over. You don’t just wonder what you believe—you wonder if there’s still a place for you among the believers. You start locking doors behind you, not to keep God out, but to protect yourself from the people who claim to speak for Him.

And here’s what undoes me: when Jesus visits his friends the evening of his resurrection, he doesn’t hide his wounds. He shows them. And those wounds weren’t given to him solely at the hands of Roman pagans or atheists. They were given to him by religious leaders. By the devout. By the faithful. The ones who thought they were defending God. It’s no wonder so many of us who carry church wounds struggle to believe—we’ve seen the damage religion can do up close. But Jesus doesn’t flinch from those scars. He brings them into the room. He offers them, not as a lament, but for healing.

It’s one thing to doubt a doctrine. It’s another to doubt your own belonging. That’s where the shame creeps in. That’s where silence takes over. You don’t just wonder what you believe—you wonder if there’s still a place for you among the believers. You start locking doors behind you, not to keep God out, but to protect yourself from the people who claim to speak for Him.

At least one disciple was absent when Jesus showed up. Thomas wasn’t there. Maybe he needed space. Maybe he couldn’t bring himself to gather with the others in the aftermath of everything they had lost. We don’t know why he was not there. But we do know this: when he heard the others’ testimony, he couldn’t fake belief. He named what he needed. He doubted, openly. And instead of being dismissed or shamed, he was sought out. Jesus came back.

That’s what steadies me most about Thomas’s story. It isn’t just that he doubted—it’s that Jesus returned for him. Not to rebuke, but to reveal. Not to force belief, but to meet Thomas exactly where he was. The same Jesus who had already spoken peace, who had already breathed the Spirit, came back for the sake of one wounded, honest soul. True love isn’t transactional. It’s not bound by efficiency. So Jesus returned—not for applause, not to defend his honor, but for one soul who still felt lost in the dark. He came back, and he showed his wounds again.

There is something profoundly gracious about that moment. Something that doesn’t get captured in debates about orthodoxy or threads about who’s in and who’s out— who is going to Heaven and who is doomed for Hell. The entire momentum of resurrection slows down for one doubting disciple. Not to punish. Not to correct. But simply to be present.

That kind of presence is rare these days. The Church, like much of the world, has grown reactive. Quick to categorize. Quick to cancel. Quick to call out. But Jesus doesn’t cancel Thomas. He doesn’t sideline him. He doesn’t question his loyalty. He meets him in his need, on his terms, with peace and with scars. Jesus does not demand performance. He offers presence.

If the Church is to be the Body of Christ, then it must also be a place where wounds are not hidden and where doubt is not exiled. We are not called to be curators of certainty. We are called to be witnesses—to the God who keeps showing up, who walks through locked doors, who brings peace to those holding their breath in fear.

If you're reading this as someone who doubts, I want you to know: you are not outside the story. You are not disqualified. Christ still comes to the room you’re in—even if it's sealed shut with disappointment or grief. His scars are not symbols of shame. They're proof of love.

That kind of presence is rare these days. The Church, like much of the world, has grown reactive. Quick to categorize. Quick to cancel. Quick to call out. But Jesus doesn’t cancel Thomas. He doesn’t sideline him. He doesn’t question his loyalty. He meets him in his need, on his terms, with peace and with scars. Jesus does not demand performance. He offers presence.

And if you are a preacher, a pastor, or a spiritual leader—consider what it means that Jesus didn’t demand belief before showing up. He came back for Thomas. He slowed down resurrection for the sake of one who was honest about his need. That’s not weak faith. That’s grace in motion.

What might it look like to lead a community that honors that kind of grace? Where doubt is held with tenderness, and where scars are not covered, but offered as testimony?

May we be that kind of Church.

May we be those kinds of people.

Wounds and all.

Good thoughts on the story, for sure. One thing that began to occur to me years ago regarding Thomas: we act as if he is the "villain." As if he was the only one who doubted. He wasn't. He was just the one willing to speak up about it. And Jesus engages the questions rather than rebuking them.

Daniel, I commented just now … May I repost this on my site (with attribution)?

Reimagine.Network