What if God Never Wanted Sacrifice?

How the story of Jesus breaks the cycle of sacrifice and violence

From the time I was a baby, I was in Christmas plays, Vacation Bible School ceremonies, puppet ministry, and eventually, the thing every Pentecostal teenager in the 1990s did: the mime and drama team. IYKYK. Despite how much I resisted at times as a youth, one of the most spiritually developmental things the church ever did for me was give me space to act out the story of God. Drama as a way of participating in the story of God was deeply formative for me. To this day, it’s the main resource my mind draws from when I think about the Christmas story or the story of Easter. I know those stories inside and out because I didn’t just hear them, I embodied them.

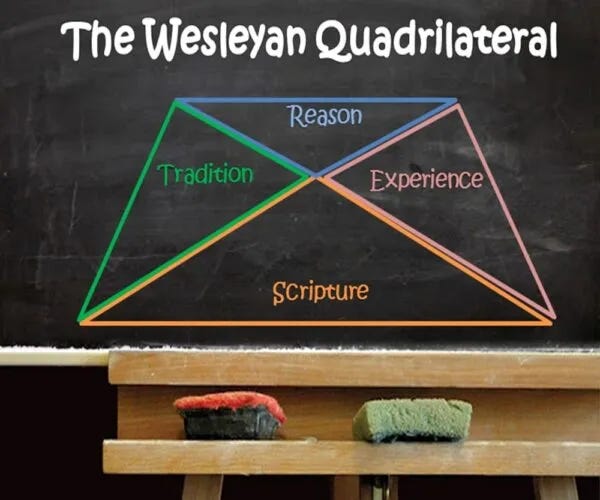

My mom wrote most of the scripts for our church productions, and she wrote them straight from the Bible. I even helped her write a few. She was our “set mama,” directing Christmas plays, executing VBS programs, leading the drama team, and carting us around to churches all over the area to share our ministry. That was how I came to know God: through participation, through embodiment, through story. And to this day, I still understand God best narratively, in the unfolding drama of life. If you know the Wesleyan Quadrilateral, you won’t be surprised to hear that I lean most heavily on experience; more than Scripture, reason, or tradition. Big surprise there. Because at the end of the day, all we have, besides a bunch of ideas, is our lived experience. And no one escapes that. Not if they want to save their soul.

One of my favorite scenes of every Christmas play was when the angels appeared to the shepherds. One year, I got to be one of those shepherds. We had a makeshift fire made of red tissue paper and a flashlight, and there were three of us gathered around it, staffs in hand. I sat in the middle. The sanctuary lights dimmed. Then, out came every little girl in the church who didn’t have a part—dressed in white robes, with halos made of Christmas tree garland, walking solemnly down the aisle. They were our heavenly host. And then, right in front of us, a tall, beautiful adult angel appeared as if she was hovering over us and spoke with authority, as if speaking directly to me:

Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord. And this shall be a sign unto you; Ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger. And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God, and saying, Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.

Luke 2:10-14

And then, suddenly, the whole room filled with voices as all the little angels lifted their arms and cried out together:

“Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.”

Then we erupted into Hark! The Herald Angels Sing, and the congregation stood to join us as the angels disappeared back down the aisle.

I heard it with my own ears: “Peace on earth, goodwill toward men.” I sang it with my own voice:

“Hark! the herald angels sing, glory to the newborn King.

Peace on earth and mercy mild, God and sinners reconciled.”

That memory lives in my bones. And somewhere deep inside, even then, I knew this was the whole point, this was the thing the gospel was always aiming at. Peace.

The story of God's mission to bring peace to the earth doesn’t begin with the New Testament. It’s there in the Hebrew Scriptures too. But right alongside it runs another thread throughout the entire Bible: a story of violence, and lots of it. Which raises the old questions: Is God two-faced? Is the God of the Old Testament different than the God of the New Testament? What’s actually going on here?

The way I’ve come to understand it is less about theology in the abstract and more about anthropology, or what it means to be human. Revelation in Scripture, I believe, comes to us not as a dropped-from-heaven manual but through the messy, unfolding evolution of our consciousness, instincts, and longings. Scripture captures humanity’s grappling with both vengeance and mercy— projecting both onto God— even as we are drawn forward into the image of a God who is Love.

The story of Jesus being born as God in the flesh doesn’t break from the Old Testament, it fulfills it by revealing its center. In Jesus, we see the clearest image of God ever given, not in abstract theology but in flesh and blood. His life, his teachings, and above all, his passion reframe our violent projections and show us what God has always been like. Jesus doesn’t just interpret Scripture; he embodies the Word. And what he reveals is that the heart of God has always been love, mercy, and peace. The kingdom he announces is not about domination, but transformation— a new kind of reality, within us and among us, waiting to be unveiled. He is the one who says the law and the prophets are fulfilled in love. The kingdom he announces is not a military operation that subjugates enemies, but a transformation of the human heart—a reality already within us, waiting to be unveiled. And that kingdom, as the angels first declared, is a kingdom of peace.

The real challenge, then, is an anthropological one: how do we become creatures of peace and not violence? The biblical story emerges from within God’s relationship with a violent species— humans with a primitive drive toward competition, envy, and murder. It begins with the first sin outside Eden, when Cain kills his brother Abel. And at the heart of that moment? The question of sacrifice.

This is the thread that runs through all human history: the drive to sacrifice someone, or some group, in order to preserve peace.

René Girard, who I consider one of the most important anthropologists and philosophers of the 20th century, made a startling discovery as he studied ancient myths and sacred texts. Beneath the rituals and religions, he found a pattern: an engine that drives human culture. He called it mimetic desire: the tendency of human beings to imitate each other’s wants, which breeds rivalry, then violence. Unlike animals, whose appetites produce competition that ends in surrender or hierarchy, humans don’t stop. Our desire is more intense, our imitation more consuming, and our violence more relentless. We don't settle into dominance, we spiral into vengeance. I kill you, your brother kills me, my cousin hunts him down, and the cycle continues. Vengeance is contagious. And when it spreads unchecked, it doesn’t just destroy relationships, it builds a culture of violence. Societies can't sustain that kind of instability, so they do something primal and horrifying: they pick a scapegoat. They direct all the tension, fear, and rivalry onto one victim. Sacrifice that one, and the peace returns for a while. Then, if we don't learn from the story we just acted out, we will repeat the cycle again. And we have been for centuries.

Mimesis, Girard suggests, is the foundation of human society. And it’s the pattern Scripture reveals and then confronts. What begins with Cain and Abel continues through generations, with altars and offerings and holy wars, until the prophets start crying out that God never wanted sacrifice at all. “I desire mercy, not sacrifice,” says Hosea (Hosea 6:6). “What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices?” asks Isaiah (Isaiah 1:11). “Let justice roll down like waters,” thunders Amos (Amos 5:24). “What does the Lord require of you?” asks Micah (Micah 6:8)— not blood, but justice, mercy, and humility.

This is where we must consider the ways our theology has become infected with the sacrificial myth. As Michael Hardin says, if we’re going to take Jesus seriously, then we have to take his hermeneutic seriously too. We must ask whether our reading of Scripture aligns with the prophetic and apostolic witness, whether our theology reflects the God revealed in Jesus, or if it’s still shaped by the logic of empire, by the old patterns of violence dressed up as holiness. Because something about committing violence in the name of redemption feels righteous. The scapegoating mechanism is rife with the moral superiority of groupthink and mob mentality.

The central question is this: What does God without violence look like? The answer, of course, is Jesus. But if Jesus is the clearest revelation of God, then we have to reconsider the sacrificial underpinnings of much of our theology. Do our doctrines require a victim? Do they justify violence in the name of holiness? Do they sanctify rivalry, create scapegoats, or preach peace while practicing exclusion?

We must ask whether our reading of Scripture aligns with the prophetic and apostolic witness, whether our theology reflects the God revealed in Jesus, or if it’s still shaped by the logic of empire, by the old patterns of violence dressed up as holiness. Because something about committing violence in the name of redemption feels righteous. The scapegoating mechanism is rife with the moral superiority of groupthink and mob mentality.

Peace is not just the end goal of the gospel. It is the way of the gospel. And the longer we cling to mythologies that sacralize violence, the longer we obscure the God who forgives, who heals, and who invites us to break the cycle once and for all.

The kingdom has already come. And it comes still, every time we choose mercy over sacrifice, and love over vengeance. It comes every time we refuse to scapegoat, every time we lay down our swords, every time we live the peace the angels proclaimed.

This is what makes the apocalyptic message of Jesus so radical. His unveiling of the kingdom does not come with fire from heaven, but with forgiveness from a cross. The true apocalypse is not about destruction, but about exposure. It is about revealing and dismantling the violent systems we have mistaken for God. Even the “wrath of the lamb,” that strange and unsettling phrase from Revelation 6, takes on a new meaning in this light; not a threat of retribution, but a radical unveiling of the world’s scapegoating machinery. The lamb’s wrath is not against people, but against the systems that keep crucifying them.

The end Jesus brings is not the destruction of the world, but the end of sacrifice, the end of scapegoating, the end of redemptive violence.

Glory to God in the highest. And on earth, peace.

Enlightening. Thanks.

The excellent translation of the New Testament by David Bentley Hart helps clarify the issue:

"For all have sinned and lack God’s magnificence, being vindicated as a gift by his grace, because of the manumission fee paid in the Anointed One, Jesus, whom God proffered on account of faithfulness as a conciliation, in his blood, as a demonstration of his justice through the dismissal of past sins." (Romans 3:23-25)