Why I Care About the Pope and Why Pentecostals Might Want To

What a Third-Stream Faith Has in Common With the Oldest Church on Earth

Last week, when the white smoke rose and the name of the new pope was announced, I got a handful of messages from friends and acquaintances: "Why does this matter?" "Isn’t he just a figurehead?" One person even asked, "Isn't the pope a false idol?"

I get the skepticism. I really do. I didn't grow up anywhere near Rome or under the shadow of papal authority. I was raised Pentecostal in the American South, where leaders looked more like crazed prophets than civilized royalty. Nevertheless, the pope’s selection matters to me. Not because I’m Catholic, but because I believe in the Church universal—and I believe the Spirit moves in more places than we expect.

To understand why the pope matters to me, you have to understand where I come from. I grew up with altar calls, anointing oil, and foot washing. We believed in miracles, tongues of fire, and the real presence of God—not just in Scripture and sacrament, but in the room. The Holy Spirit wasn’t a doctrine to us. They were a person we knew, someone who moved among us when we sang and shouted and waited.

My first experience of Catholic worship was in an Episcopal Church. When I was in a season of deep doubt and spiritual exhaustion, the fires of Pentecost didn't meet me where I needed them most. Instead, I needed the predictability and repetition of the Episcopal liturgy. I started going to a local parish, kneeling beside strangers, reciting prayers that had been spoken for centuries. I needed communion. I needed to taste something grounded and ancient. It was there, in the slow rhythm of the liturgy, that I began to heal. The bread and wine didn’t replace the altar calls I was used to. They reinterpreted them.

Episcopal worship is considered Catholic because it retains many elements of the ancient liturgical and sacramental traditions of the early undivided Church. Though it is not Roman Catholic, it remains deeply shaped by the catholic tradition: the weekly Eucharist, the use of the Book of Common Prayer, the liturgical calendar, and a theology that sees communion, baptism, and holy orders as means of grace. The Episcopal Church descends from the Church of England, which aligned with Protestant reformers more for political expediency than for a full theological break. Episcopalians are essentially the American expression of that heritage—a Protestant church with Catholic bones.

What I experienced in that Episcopal parish opened a door. It showed me that ancient practices, sacred objects, and holy repetition weren’t dead traditions—they were ways people had sought God for centuries. That realization softened something in me. It made me more open to Catholicism—not as a system of hierarchy, but as a long, lived testimony to the same hunger for God that I carried.

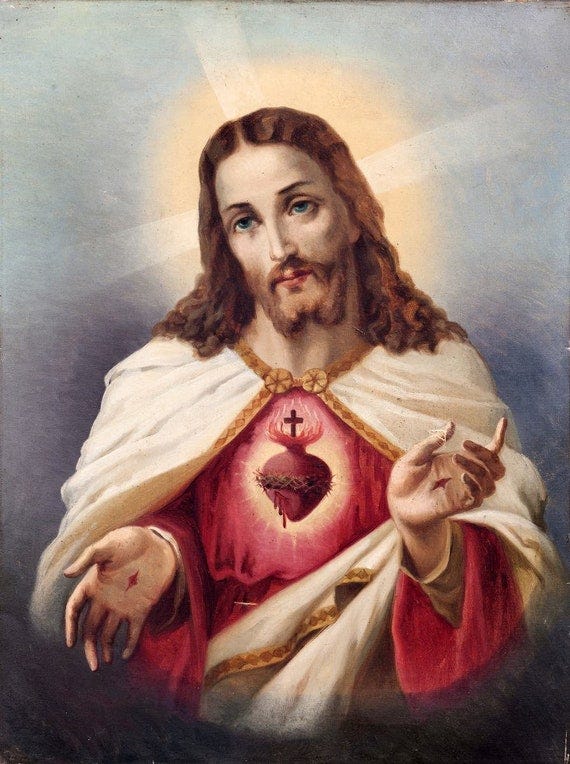

My own family’s history carried hints of Catholic presence, even if we didn’t name it that way. My grandmother was from England, where Catholicism was a dominant faith tradition in the mid-20th Century. In my grandmother’s house hung a picture of the Sacred Heart of Jesus that had been blessed by a local priest during World War II. He had gone door to door offering prayers over homes in a time of great fear. That image eventually made its way to my mother’s house, where it still hangs. In another story from England, a priest prayed over my great-uncle’s injured leg, and he was healed. These aren’t things we theologized growing up; they were simply received as signs that God hears and helps, no matter who is doing the praying.

I know Catholic doctrine differs from mine in many places. But I also know this: both Catholics and Pentecostals believe that God shows up. That God moves through bread and oil, through words and water. That sacraments are not just rituals, but encounters. We both believe in holy things.

In fact, I find the intersections of Pentecostalism and Catholicism to be far more compelling than its intersections with Protestantism. Pentecostals are not just Protestants who speak in tongues, mind you. We don’t trace our roots back to Luther or Calvin. Our roots are wild, but in the soil of Church of England and John Wesley, who was an Anglican priest. We’re not just another offshoot of the Reformation. We came out of the margins—from storefronts, tent revivals, and cottage prayer meetings. We are, in many ways, a third stream. A wilderness movement. Not Catholic. Not Protestant. Something else. Something raw, Spirit-birthed, and deeply sacramental, even if we don't use that word.

We have our own liturgies. Our own sacraments. A prayer cloth passed to a cancer patient. The washing of one another's feet. A testimony that opens the floodgates of emotionalism in a church service. And just like in any tradition, those things can be hollow or holy. We know the difference. If you participate in Pentecostal worship long enough, you will find there is just as much dead religious form in some shouting as their in some Masses.

Just as Pentecostalism intersects with Catholicism in many ways, it diverges from mainline Protestantism. Protestants define their theology by the five solas of the Reformation: sola scriptura (Scripture alone), sola fide (faith alone), sola gratia (grace alone), solus Christus (Christ alone), and soli Deo gloria (glory to God alone). These are powerful convictions. But for Pentecostals, they never quite told the whole story.

Take sola scriptura (Scripture Alone), for instance. Pentecostals love the Bible. We preach it, memorize it, testify from it, and build our lives around it. But we also believe that the Spirit still speaks—through dreams, through prophecy, tongues and interpretation, and through the gathered body. We were never comfortable limiting revelation to the written Word alone. We don't reject the Bible. We just refuse to silence the Spirit in the name of textual control.

And sola fide (Faith Alone)? Yes, we believe in faith—but not as mental assent. For us, faith is visceral. It moves. It shouts. It heals. Our people didn’t come to faith through catechisms and creeds but through altar calls and divine encounters. We are a mystic people. The language of doctrine alone could never contain our experience.

At the same time, Pentecostalism is not anti-Protestant. We have been deeply shaped by the traditions that came before us. We sing the hymns of the Reformation, preach from the Bible translated by Protestant hands, and owe much to the revivalism that came through Protestant awakenings. But we also carry a suspicion of systems that try to define or contain the Spirit. Our theology is porous, sometimes messy, and always mystical. We may share some Protestant commitments, but we diverge in tone and posture. We look for the Spirit not just in text and tradition, but in tears, tongues, and testimony.

But I also think there's a challenge here for Pentecostals. We have often been so reactive to Catholic structure or Protestant precision that we’ve failed to appreciate the depth and breadth of what it means to be part of the *Church, *with a capital C. We’ve inherited an instinct to separate—sometimes out of conviction, sometimes out of pride—and in doing so, we’ve risked cutting ourselves off from the witness of Christians who don't look or worship like us.

That brings me to the word catholic. I grew up thinking it meant Roman Catholic, full stop. But over time, I learned what many theologians and creeds meant by it: catholic means universal. The Church catholic isn’t confined to one denomination or tradition—it is the whole body of Christ throughout time and space, imperfect and diverse, but held together by the Spirit.

The Roman Catholic Church post Vatican II (1962-1965) expresses an openness to this reality as well. Before that council, the Catholic Church didn’t know what to do with people like me. Non-Catholics weren’t really considered part of the Church. But Lumen Gentium introduced a shift. It spoke of "separated brethren" and acknowledged that the Spirit might move outside the formal bounds of Rome. That language gave us all room to breathe the same air despite living in different theological realities.

And maybe that’s what this is about for me—seeing the Spirit in the wild. I don’t need to become Catholic to honor the beauty and depth of that tradition. And Catholics don’t need to become Pentecostal for me to call them family. We may speak in different tongues—Latin, English, glossolalia—but we cry out to the same God.

So yes, when the pope is chosen, I watch. I pray. I hope. Not because I think he is the most holy voice or person in the church, but because I believe we are all part of something bigger than our denominations. The Spirit does not belong to one stream. They move across the aisle. Always has. Still does.