Wrestling, Worship, and the Politics of Performance

When Pentecostal Preaching, Pro Wrestling, and Political Theater Collide

I was scrolling through Facebook when I came across a post from my former denomination. It was a picture of a woman holding a wrestling-style championship belt with the words "Church of God Team Member of the Month" engraved on it. It immediately struck me as both funny and strangely fitting. A championship belt. In the Church of God. And the more I thought about it, the more I realized it made perfect sense.

I grew up on wrestling and worship. Every Saturday morning, I watched wrestling on TV. Every Sunday morning, I watched Jimmy Swaggart with my family. Pentecostal preachers always reminded me of wrestlers. They screamed, scared you, made you think they could charge hell with nothing but a water pistol. They were charismatic, larger-than-life, and, like the best wrestlers, they knew how to work a crowd. Good preachers—like good wrestlers—knew how to make you feel something. They knew how to sell the stakes, identify the villains, and rally the congregation around a common cause. But just like in wrestling, sometimes the "good guys" weren’t always good, and the "bad guys" weren’t always bad. In wrestling, heroes and villains are often assigned roles, but those roles shift. A beloved hero can turn heel with a single act of betrayal, while a longtime villain can win over the crowd and be seen in a new light. The same is true in Pentecostalism. Preachers, often framed as righteous figures, can be deeply flawed, even manipulative. Meanwhile, those labeled as dissenters, doubters, or troublemakers may be the ones actually speaking truth. The performance of righteousness can mask real corruption, just as the persona of a villain can hide an honest heart.

Chris Hedges, in Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle, argues that American culture has surrendered reality to illusion. In his opening chapter, he explores how professional wrestling functions as a modern mythology, a scripted spectacle that, though artificial, resonates deeply with its audience. Fans participate in kayfabe—the suspension of disbelief that allows them to immerse themselves in the drama, knowing on some level that it’s all a show. Hedges sees this as emblematic of a broader societal trend: politics, religion, and media have all become arenas where spectacle has overtaken substance, where reality is rewritten to fit emotional narratives, and where the performance itself has become the product.

The image of Hulk Hogan, in full character, stepping onto the stage at the Republican National Convention, for instance, was a full-circle moment. It wasn’t just a celebrity cameo; it was the culmination of decades of political transformation, where the logic of wrestling-style storytelling had fully infiltrated the highest levels of power. Hogan, a larger-than-life persona built on good-versus-evil simplicity, didn’t just represent wrestling—he represented the way American politics had become more about theatrical narratives than governance. The absurdity of it wasn’t a break from political theater; it was the logical endpoint of a culture that had long been moving toward spectacle-driven governance, where performance and entertainment had become indistinguishable from leadership and policy.

Politics had already become a form of kayfabe long before Hogan stepped onto that stage. His presence didn’t corrupt the political process; it revealed what politics had already become—a space where identity, narrative, and emotion mattered more than policy or governance. It was the full realization of what Hedges argues in Empire of Illusion: that we now live in a society where entertainment has supplanted reality, where politics functions like professional wrestling, complete with heroes and villains playing pre-scripted roles.

And if that sounds familiar to you, my Pentecostal brothers and sisters, it should.

As someone who loves both professional wrestling and Pentecostal preaching, I recognize the power of spectacle. Wrestling, at its best, is storytelling in its rawest, most theatrical form, capable of evoking deep emotions and allegiances. Pentecostal preaching, when grounded in sincerity, is an art of spiritual engagement, a way of bringing people into a shared experience of the divine. But when spectacle becomes the purpose rather than the means, something fundamental is lost. The performance overtakes the message. The anointing is confused with the show. We begin to serve the spectacle rather than God.

The performance overtakes the message. The anointing is confused with the show. We begin to serve the spectacle rather than God.

Pentecostal preachers, much like wrestlers, often engage in their own form of kayfabe. Within Pentecostalism, the ‘anointed’ preacher is often a heightened version of themselves—a larger-than-life figure who moves, speaks, and reacts in a way that would seem exaggerated outside the pulpit. Congregants, in turn, participate in this shared illusion, knowing on some level that the preacher is performing, yet embracing the emotional reality it produces. The shouting, the pacing, the rhythmic call-and-response—all of it is an art form, not unlike the way a wrestler “works the crowd.” This is not a criticism. It is a recognition of how human beings respond to performance and how deeply it can shape belief. But when Pentecostalism as a movement becomes more invested in the performance than in genuine spiritual formation, we lose our way. The shift from reality to spectacle is subtle, but once it happens, we are trapped in kayfabe.

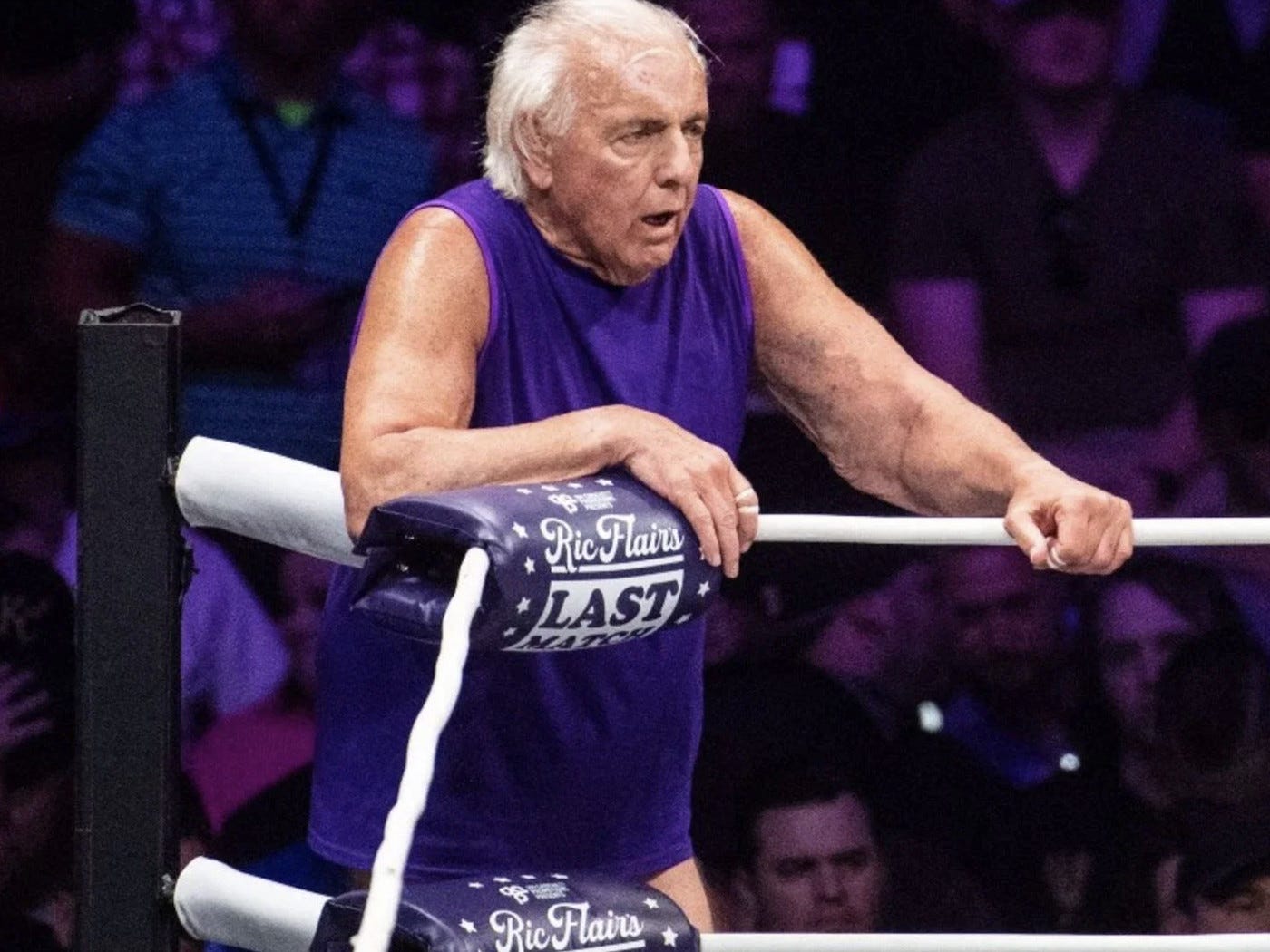

Ric Flair provides a perfect case study in what happens when kayfabe consumes the man. “The Nature Boy” was a character, but over time, there ceased to be a distinction between Ric Flair the person and Ric Flair the gimmick. The limousine-riding, jet-flying, Rolex-wearing persona became his whole identity, leading to personal and financial ruin, multiple divorces, and a physical toll that he carries to this day. The man got lost in the performance. He no longer played the role; he was the role, to his own detriment. The same has happened to Pentecostalism as an institution. What once may have been an anointed movement of the Holy Spirit has, in many circles, become an unbreakable performance. The preacher is no longer just an instrument of God’s presence but a character in a spectacle. The show must go on, even when the spirit has left the building.

Pentecostalism has become kayfabe, a political wrestling match where the good guys and bad guys are assigned their roles, and the outcome is determined not by truth but by whatever keeps the audience engaged.

And now, that confusion between spectacle and substance has led to Pentecostalism’s increasing alignment with political power. Pentecostal leaders now have more access to the White House than ever before, but at what cost? The refusal to rebuke false prophets like Paula White, the growing belief that Pentecostals have a direct role in “restoring America to God,” the prophetic proclamations that certain politicians are ‘anointed’ by divine decree—all of it points to a movement that has abandoned reality for illusion. Pentecostalism has become kayfabe, a political wrestling match where the good guys and bad guys are assigned their roles, and the outcome is determined not by truth but by whatever keeps the audience engaged.

Hedges warned that this is where spectacle inevitably leads: to a world where reality is dictated by performance, where truth is irrelevant, and where those who control the narrative—whether in wrestling, the pulpit, or politics—hold the real power. The danger is not in enjoying the show but in forgetting that it is a show. We can love wrestling, we can love Pentecostal preaching, but we must not be deceived into believing that kayfabe is reality. Because once we do, we are no longer serving God—we are just part of the performance.